MPI | 24.08.2017

By Angelo Scotto

Since its unification in the 19th century, Italy has been a country of emigration, with millions of Italians migrating to the Americas and elsewhere in Europe for economic and political reasons. Smaller numbers also headed to North Africa during the country’s period of colonialism. Italians have accounted for the largest voluntary emigration in recorded history, with 13 million leaving between 1880 and 1915. And Italian mobility also spanned major internal migration from poorer areas in the country’s South to its wealthier North.

Against the historic backdrop of emigration, newer patterns have manifested, making Italy a destination for migrants, whether for permanent settlement or as a way station. Shifting demographics that began in the mid-20th century translated into increased demand for foreign workers even as external factors, including the decline of the Soviet bloc, acted as push factors for migration toward wealthier countries, among them Italy. More recently, political and economic developments far beyond Italy’s borders have brought inflows of asylum seekers and migrants from diverse regions, including Eastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

By accident of geography, Italy has played an outsized role in the current European migration crisis, receiving more than 335,000 irregular arrivals via the Mediterranean during 2015-16. Flows during the first half of 2017 outpaced those over the same period a year earlier, presenting Italy and the European Union new challenges in curbing asylum seeker and migrant journeys across the often treacherous sea. As a peninsula in the middle of the Mediterranean, Italy represents a logical passage for maritime arrivals who intend to move onward to reunite with relatives or find work in Germany, Sweden, and other Northern European countries. Since the collapse or destabilization of authoritarian regimes in North Africa and the Middle East following the Arab Spring in 2011, growing numbers of people fleeing civil war and instability have departed for Europe, a phenomenon that came to a head in 2015 and 2016 as EU countries were overwhelmed by the scale of new arrivals. Italy, Greece, and the Balkan countries have represented the first destinations for these asylum seekers, and under European asylum regulations, must provide them with reception and assistance.

Where Italians once departed in massive waves before and after world wars, and to escape poverty or organized crime, the country more recently has witnessed shifting patterns of inflows and outflows. Changing economic realities in recent years have meant economic migration to Italy is decreasing, and some immigrants who had established themselves are returning to their homeland. Italians themselves continue to move internally and abroad, due to several factors: the stagnant labor market, marked by a high level of youth unemployment; lack of social mobility; and persistent regional social and economic disparities.

This article provides an analysis of Italy’s history of emigration and immigration, and examines contemporary debates, including the country’s evolving role in the reception of asylum seekers.

From Large-Scale Emigration to Becoming a Destination Country

Italy’s migration history, once characterized largely by emigration, has grown increasingly complex since the 1800s, as this section explores.

Emigration

Italian emigration was driven mainly by economic factors. After the unification of the country in 1861, crises in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors dramatically reduced incomes for the rural population and launched the first migration flows. Emigration remained high in the following decades, owing to the inability of the Italian economy to generate enough jobs.

Beginning with Italy’s unification, emigration trends can be divided into three main periods. In the first period, from the 1860s to the end of the century, nearly 7 million migrants left Italy, primarily for other European countries. Then, from 1900 to 1928, 12 million Italians migrated, mostly toward non-European countries such as the United States, although after World War I emigration within Europe rose again. During the third period, from 1946 to 1965, more than 5 million Italians emigrated, mainly to neighboring countries such as Germany and Belgium.

Internal Migration

Italian internal mobility has two main dimensions, both fueled by the shrinking agriculture sector and growing labor demand in manufacturing. The first is urbanization, which began in the 19th century, continued in the following decades and during the Mussolini era (despite the regime’s attempt to stop it), and accelerated after World War II. Between 1951 and 1971, the share of Italians living in rural areas and small towns fell from 24 percent of the overall population to 13 percent.

A second and more uniquely Italian dimension of internal migration is movement from Southern and island regions to Central and Northern areas. These flows were particularly strong in the 1950s and 1960s, and declined in subsequent decades. On the whole, internal migration after World War II caused massive social change, from the rise of overpopulated metropolitan areas in Turin, Rome, and Milan, to the depopulation of rural areas, mainly in the South.

Immigration

Many Italians who had gone abroad returned in the post-war period, with 3 million coming home between 1946 and 1970. Alongside continued returnee flows, Italy began to experience its first significant immigrant arrivals in the 1970s. As with other European countries, Italy has been on the receiving end of post-Fordist migration flows since 1973-74, driven by the beginning of a shift in the industrial world from mass production toward greater specialization and the move toward greater economic diversification. Immigrant workers shifted from central sectors of the economy (e.g. industry) to more niche ones, such as domestic and janitorial work, construction, and harvesting.

In the case of Italy, regional socioeconomic differences shaped immigrants’ geographic and labor market distribution. In the 1970s, Filipino migrants began arriving to work in the home-care sector. During the 1980s, immigrants started coming from the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. However, it was only at the end of the decade that the perception of Italy as a country of immigration started to catch on, mostly after the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Thousands of people fleeing Albania reached Italy on overcrowded boats, and media reports of these events generated both solidarity and fear among Italians.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the immigrant population increased rapidly. At the end of 2010 there were 4,570,000 foreign residents, comprising 7.5 percent of the population, up from 1,549,000 (2.7 percent) in 2002 and 2,939,000 (5 percent) in 2006. Although Albanians and Moroccans were for many years the main origin groups, Romanians quickly outpaced them after Romania joined the European Union in 2006. Nearly 969,000 Romanians legally resided in Italy in 2010.

Unlike today, refugees and asylum seekers were a negligible fraction of migration flows to Italy in the 20th century: Over the 14-year period beginning in 1985, for example, Italy received approximately 100,000 asylum applications, with generally fewer than 30,000 filed annually from 2000-10. By comparison, Europe received 697,000 asylum applications in 1992 alone.

Development of Migration Policies

The first Italian laws on immigration were known informally as the Foschi Law (1986) and the Martelli Law (1989). Both were relevant in acknowledging rights for migrants and improving the status of foreign workers and their families. However, they were ineffective in regulating economic migration flows and reducing irregular migration, because they did not provide enough resources for reception and assistance or for enforcing the expulsion of irregular migrants. The inability to systematically deal with irregular immigration resulted in the frequent use of sanatorie (annulments) in order to legalize the status of foreigners living in Italy.

Despite these problems, the Martelli Law remained unchanged until 1998, when the center-left government approved, after a year-long parliamentary debate, the Turco-Napolitano Law. This law separated for the first time humanitarian issues from immigration policy, and tried to balance civil-society pressures on integration and refugees with demands for more effective control over illegal immigration. The law’s main provisions remain in force, with several amendments—primarily to make it stricter. The first was in 2002, when the new center-right government passed the Bossi-Fini Act, extending temporary detention of unauthorized migrants and reducing the tools for integration. The law restricted family reunification to spouses and dependent children, and lengthened the period of legal residence required to gain eligibility for permanent residence.

The center-right coalition took a further step in 2009, when it introduced the “safety package,” a set of laws to crack down on unauthorized immigrants from other EU Member States. Those affected by the laws included ethnic Roma, who already faced severe discrimination under national and local policies clearing out their settlements and relegating them to segregated camps. Controversially, the legislation made illegal immigration a felony and allowed municipal governments to organize security patrols. While the purpose of the patrols was simply to watch public areas and inform police about possible infractions, nonprofits and the opposition criticized them as legitimizing public, anti-migrant mobs.

Between 2010 and 2013, fallout from the international economic crisis pushed immigration to the background in Italian politics, and there were no significant migration reforms. However, the subject became relevant again with the onset of the European refugee crisis in 2015. Italy has been ruled by coalition governments since 2011, and policymakers have followed a dual path when dealing with immigration. On the one hand they have asked the European Union and other Member States for greater cooperation and solidarity in reception and care for asylum seekers; on the other, they have enforced stricter measures for controlling irregular flows and have clashed with Brussels and individual Member States. The Minniti Decree, approved in April 2017, aims to speed up the application process for asylum seekers and to distinguish them from unauthorized immigrants. The decree bars rejected asylum seekers from a second appeal, and took steps to increase the number of detention centers and introduce voluntary work for asylum seekers.

Balancing Humanitarian and Security Concerns

As demonstrated by the evolution of Italian migration laws since the early 2000s, immigration has been viewed mostly as a security problem. Center-right and right-wing parties have politicized the issue, framing immigration as a threat; conversely, center-left parties sometimes try to portray immigration as a resource, but mostly seek to depoliticize the issue or shift the agenda elsewhere. The security narrative has proved resilient enough to spread across the political spectrum, as shown by the Minniti Decree, whose authors belong to the center-left Democratic Party.

The focus on security, however, does not mean that Italy lacks provisions for the reception, assistance, and integration of migrants. While the willingness of policymakers to act on these issues varies greatly by city and region, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across Italy are deeply committed to charity and advocacy for migrants. However, even NGOs are not immune to the shifting tides of public opinion. While media and policymakers acknowledge the key role of NGOs in migration management, in recent years populist and right-wing parties and media outlets have accused them of turning migrant assistance into a business, following inquiries into their rescue and reception activities. Setting aside the results of these inquiries, some of which remain ongoing, accusations against NGOs appear to be the consequence of a wider anti-immigration shift that has emerged as a result of politics and the way Italian media have covered immigration.

Such public sentiment has also heavily influenced reform of the citizenship law, which since 1992 has been based on the jus sanguinis principle, or nationality by bloodline. Migrants must have ten years of legal residence to qualify for citizenship, and their children, even if native born, must wait until they turn 18 to become eligible. Moreover, even when these criteria are fulfilled, citizenship is not automatically granted, and the decision is at the discretion of the government. Policymakers have made several attempts to reform the law and introduce the jus soli principle (nationality by birthplace), but they always meet strong resistance from right-wing parties and find little public support. In 2017, however, a new law was approved, based on “moderate jus soli” (Italian-born children can apply for citizenship if at least one parent has a permanent residence permit) and jus culturae (children who arrived before age 12 can apply for citizenship if they have regularly attended school in Italy for at least five years).

Notably, while immigration is greatly politicized and debated in Italy, emigration is almost absent from the political agenda. The last important reforms concerning diaspora relations happened in 1992, when some descendants of Italian migrants became eligible to obtain citizenship, and in 2000 Italians abroad gained the right to vote in referendums and general elections.

Otherwise, current Italian emigration has received little attention, although the number of Italians leaving the country has increased again in recent decades. Italian emigration is sometimes covered by newspapers and television shows, which usually focus on the issue of brain drain. So far, with the exception of sporadic measures to encourage Italian scholars abroad to return, there have been no significant interventions by the national government to tighten its bonds with emigrants.

Migration in Italy Today

The New Italian Emigration

Emigration slowed in the 1970s, when the number of Italians leaving fell to historic lows while returns peaked. However, in the last two decades emigration has increased again, accelerating after the eurozone economic crisis struck Italy in 2011. Registrations of Italians abroad jumped from 3 million in 2006 to more than 5 million in 2016, according to data from the Registry of Italians Resident Abroad (AIRE); moreover, since 2010 emigration has been consistently increasing, while returns have been steady.

The new Italian emigration is socially and demographically diverse. More than half of emigrants today come from the Southern regions of Italy, but emigration from other areas is increasing. The gender composition is balanced, with a slight prevalence of men. Emigrants are, on average, young. The elderly (over age 65) comprise just 20 percent of emigrants registered with AIRE, even as they represent 24 percent of the Italian population; this was the only age group with declining emigration in 2015. Conversely, emigrants ages 18 to 34 are the largest group, and those under 30 almost doubled from 2011 to 2015.

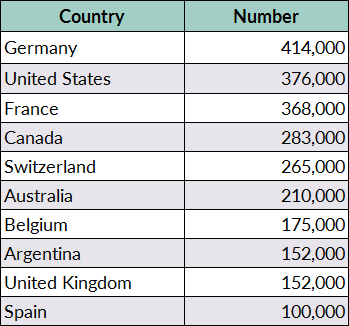

Most migrants head elsewhere in Europe, mainly Germany, France, and Switzerland (see Table 1). Europe accounts for nearly 54 percent of Italians abroad and 69 percent of people leaving Italy in 2015. While EU free movement facilitates migration, on its own it is not enough to explain the acceleration of emigration in the past several years. As in the past, economic causes are the most relevant factors. However, outflows of the highly skilled are a stronger component of migration today than in the 19th century and before the 1960s, when emigrants typically belonged to the lower classes and were employed in low-skilled jobs. Nowadays, college-educated Italians look abroad for high-skilled jobs they cannot find at home.

Besides workers, a number of Italian retirees have settled in countries with a lower cost of living. While the number of Italian pensioners abroad fell by almost 10 percent from 2003 to 2015, there have been significant increases in movement to Eastern Europe, attractive for its lower prices of goods and services.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the mixed trends for Italian students abroad. While the enrollment of Italian undergraduate students in foreign universities decreased significantly in 2013, after rising consistently over the previous decade, the number of Italian international students at all levels has been consistently increasing. The number of high school students participating in long-term study abroad grew 55 percent from 2010 to 2013.

Diversifying Immigration

At the start of 2016, slightly more than 5 million foreign citizens legally resided in Italy, comprising about 9 percent of the population of 60.6 million people. In comparison, just under 3 million migrants lived in Italy in 2006, and slightly more than 4.5 million in 2010. The number of migrants increased steadily during the 1990s and the 2000s, but slowed after 2011 because of the economic crisis.

Foreigners in Italy come from 196 countries, with Europe accounting for slightly more than half (see Table 2). While in the 1970s and early 1980s migration flows were mainly from South and Central America and Southeast Asia, in subsequent decades immigration has diversified and flows from Eastern Europe and North Africa have become predominant. The overall immigrant population is balanced gender-wise, with women comprising roughly 53 percent. However, there are significant differences from one national group to another, with men accounting for the majority of migrants from the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, while women are over-represented among Eastern European migrants.

Immigrants in Italy are younger on average: 21 percent are under age 18, compared to 16.4 percent of the overall Italian population; 44 percent are ages 18 to 40, in contrast with 25.9 percent of the entire population; and just 3 percent are over age 65, compared to 22.3 percent overall. Nearly 73 percent of all resident children of migrants were born in Italy, with higher shares among younger age groups.

Of the total migrant population, 1,681,000 had temporary residency permits, primarily students and workers. This category includes a small group of seasonal workers, usually employed in tourism and agriculture. In 2015, fewer than 4,000 seasonal work permits were issued, representing just 1.6 percent of all temporary permits; however, these data do not include much larger numbers of unauthorized seasonal workers, mainly employed in agriculture in the South. These workers usually arrive in July and stay until November, moving to different regions and provinces to work as farm laborers on several harvests.

Seasonal laborers in the South are often victims of the so-called caporalato, an illicit form of employment mediation in which recruiters use their power to extort money from workers for board, lodging, and transportation. Each season, it is estimated that thousands of workers are exploited by the caporali; this criminal phenomenon is one of the main migration-related problems in Southern Italy, sparking many protests among migrants and natives alike.

It is difficult to determine the overall number of unauthorized immigrants since they either arrive in Italy clandestinely or overstay a tourist visa. The most recent estimate from Fondazione ISMU puts the number at approximately 435,000 in 2016. These numbers do not include asylum seekers, who, despite often using irregular channels to arrive in Italy, belong to a separate category.

On the Frontlines of the Refugee Crisis

Historically, Italy has never hosted many refugees and asylum seekers compared to other European countries. This changed after 2011, when the Arab Spring and collapse of regimes in Tunisia and Libya led to a significant rise in the number of asylum seekers—a phenomenon called the North Africa Emergency. Italy received 37,000 asylum requests in 2011, 17,000 in 2012, 27,000 in 2013, and 45,000 in 2014. A far greater jump in the numbers of migrants and asylum seekers arriving in Europe occurred in 2015, as civil war in Syria and other humanitarian crises drove more than 1 million people to the continent. In Italy alone, 154,000 asylum seekers and migrants arrived in 2015 and 181,000 in 2016. However, as in earlier years the majority of these were not from the countries struck by violence and unrest in the Middle East, but sub-Saharan Africa.

While EU regulations require that asylum seekers submit their application in the first Member State they reach, in practice many seek to avoid submitting their documentation in Italy, hoping to file once they reach their preferred destination. But because a number of countries have reintroduced border controls to avoid mass arrivals, Italy has had to handle a large share of the asylum seekers as the European Union continues to struggle to implement its redistribution agreement.

The Italian government has carried out several initiatives for handling arrivals by sea and managing the reception and assistance of asylum seekers. After 366 migrants died in a shipwreck near the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013, the government launched Mare Nostrum, a humanitarian and military operation to rescue ships carrying asylum seekers. Mare Nostrum was ended in November 2014 and replaced by Operation Triton, led by the EU border control agency Frontex. While Triton had a narrower mandate and less funding than Mare Nostrum, the Italian government, which had long asked for a more supportive EU approach to the maritime arrivals, viewed the change in responsibility as a success. With flows shifting to the eastern Mediterranean route (which goes through Turkey to the Greek islands and onward to Bulgaria or Cyprus) in 2015, Italy had something of a reprieve. But after border closures in the Balkans and the signing of the EU-Turkey deal in early 2016, the Central Mediterranean again saw more traffic. Thousands of migrants have died in recent years attempting the perilous sea crossing, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

The Italian government places asylum seekers throughout the provinces, proportionally to population size. At the provincial level, law enforcement agencies (prefectures and central police stations) register asylum seekers and move them to reception centers, in cooperation with local health agencies, civil protection, and nonprofit organizations. The lack of adequate resources and facilities represents the main limitation of this system; many asylum seekers have been housed in hotels and private residences, sometimes in mountainous areas or rural towns where it is difficult for them to comply with asylum application requirements. Moreover, the regional allocation has generated tensions between national and local governments, over insufficient resources. Finally, the increase in arrivals and applications has overloaded state agencies with work; as described above, in response, the Minniti Decree has attempted to simplify protection procedures.

While the numbers of arrivals in other parts of Europe, including Greece, have fallen dramatically since the height of the migration crisis, they remained high in Italy in the first half of 2017, though they decreased sharply in July and August. Once again, Italian policymakers pleaded with EU officials for further assistance in managing the flows of primarily African migrants, even threatening to close Italian ports to humanitarian ships flying foreign flags. Other strategies to stem the flows included deals with North and sub-Saharan African countries, most notably a controversial one with Libya’s fragile government to reduce boat crossings, which was suspended by a Libyan court. Italy also struck a cooperation agreement with Tunisia to tackle illegal migration and human trafficking, and deals with Chad and Niger to set up reception centers in their territories. These strategies, however, have been largely ineffective. Meanwhile neighbors, including Austria, have closed their borders to prevent migrants from moving northward, and other Member States such as Poland and Hungary continue to refuse to take in asylum seekers to relieve the burden on frontline countries.

Issues on the Horizon

The political response to immigration challenges in Italy, as discussed earlier, has mainly focused on the security dimension, and the legislation approved since the 2000s has centered on restricting illegal immigration. Policymakers have shown little interest in the integration of permanent residents and their Italian-born children: Citizenship reform has been slow and torturous, and its final version, although moderate, remains an object of significant criticism, and not just from right-wing parties. According to a 2017 survey, the majority of the public is against reforming the citizenship law, a reversal from 2011. These negative opinions may be reinforced by an inflated perception of the number of migrants in Italy: In 2015, Italians on average thought migrants represented 26 percent of the population, according to a survey by Ipsos MORI; in reality, they accounted for 9 percent.

Hostility to immigration is not an issue unique to Italy. Across the West, parties, movements, and candidates who placed opposition to immigration at the core of their platforms have grown in strength and number. So far, the main result of this trend in Europe is the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum, in which British voters chose to leave the European Union. Italians in the United Kingdom, as with other EU nationals there, remain fearful about their place in a post-Brexit future that is still being negotiated. The possibility that other countries may restrict EU migration flows is worrisome for Italy, because recent emigration has helped to reduce internal social tension. This is why the Italian government has joined other Member States in supporting the right of EU citizens to remain in the United Kingdom.

Despite the challenges, immigration and emigration are expected to retain a relevant role in Italian society, particularly concerning demographics. The Italian population, which has experienced a low birthrate, is aging quickly. Migration has been essential in slowing this trend, as a number of studies have shown. In addition, a younger, more active immigrant population is essential for sustaining Italy’s welfare and pension system. Finding the proper balance between the country’s need for migrants and voters’ negative attitude toward them will be a key challenge for Italian policymakers in the decades to come.

Sources

Ambrosini, Maurizio. 2005. Sociologia delle Migrazioni. Bologna, Italy: Il Mulino.

ANSA. 2014. Italian Students Flock Abroad to Study. ANSA, October 1, 2014. Available online.

Barbieri, Francesca. 2016. Number of Young Italian Expats on a Steady Rise, up 95% in 5 Years. Il Sole 24 Ore, August 4, 2016. Available online.

Berry, Mike, Inaki Garcia-Blanco, and Kerry Moore. 2015. Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: A Content Analysis of Five European Countries, Report prepared for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Cardiff, UK: Cardiff School of Journalism, Media, and Cultural Studies. Available online.

Bocchi, Alessandra. 2017. Tunisia and Italy Sign Deal on Illegal Immigration, Agree to Support Libya. Libya Herald, February 9, 2017. Available online.

Bonifazi, Corrado and Frank Heins. 2000. Long-Term Trends of Internal Migration in Italy. Population, Space and Place 6 (2): 111-31.

Centro Studi e Ricerche IDOS. 2016. Dossier Statistico Immigrazione 2016. Rome: IDOS Edizioni. Available online.

Centro Studi Emigrazione – Roma (CSER). 1975. L’Emigrazione Italiana negli Anni ’70. Rome: CSER.

Choate, Mark I. 2008. Emigrant Nation: The Making of Italy Abroad. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Connor, Phillip. 2016. Number of Refugees to Europe Surges to Record 1.3 Million in 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online.

Dal Zotto, Emanuela and Angelo Scotto. 2014. Dall’Emergenza alla Rete. Pavia, Italy: Province of Pavia. Available online.

Doctors Without Borders. 2008. Una Stagione all’Inferno. Rome: Doctors Without Borders. Available online.

Einaudi, Luca. 2007. Le Politiche dell’Immigrazione in Italia dall’Unità a Oggi. Bari, Italy: Laterza.

Faini, Riccardo and Alessandra Venturini. 1994. Italian Emigration in the Prewar Period. In Migration and the International Labor Market, 1850-1939, eds. T.J. Hatton and J.G. Williamson. London: Routledge.

Fondazione Iniziative e Studi sulla Multietnicità (ISMU). 2016. Ventiduesimo Rapporto sulle Migrazioni 2016. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Fondazione Migrantes. 2016. Rapporto Italiani nel Mondo 2016. Todi, Italy: Editrice Tau.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 101,266 in 2017; 2,297 Deaths. Press release, July 7, 2017. Available online.

Ipsos MORI. 2015. Perils of Perception 2015. London: Ipsos MORI. Available online.

Katsiaficas, Caitlin. 2016. Asylum Seeker and Migrant Flows in the Mediterranean Adapt Rapidly to Changing Conditions. Migration Information Source, June 22, 2016. Available online.

Monticelli, Giuseppe Lucrezio. 1967. Italian Emigration: Basic Characteristics and Trends with Special Reference to the Last Twenty Years. International Migration Review 1 (3): 10-24. Available online.

National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). 2017. Forme, Livelli e Dinamiche dell’Urbanizzazione in Italia, Rome: ISTAT. Available online.

Prentis, Jamie. 2017. Migrant Reception Centres to be Set up in Chad and Niger. Libya Herald, May 22, 2017. Available online.

Scherer, Steve and Gabriela Baczynska. 2017. Italy Pleads to EU for Help with Migrants, Threatens to Close Ports. Reuters, June 28, 2017. Available online.

UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2017. Outbound Internationally Mobile Students by Host Region. Accessed August 21, 2017. Available online.

Zincone, Giovanna and Luigi Di Gregorio. 2002. Il Processo delle Politiche di Immigrazione in Italia: Uno Schema Interpretativo Integrato. Stato e Mercato 66 (3): 433-65.