Alle Schengenstaaten melden, dass sie inzwischen vollständig Eurosur unterstützen. Diese formelle Unterstützungsprozedur dauerte ein Jahr. Eurosur dient dem erklärten Ziel, die Bootsflüchtlinge im Mittelmeer oder bereits an den nordafrikanischen Küsten aufzuspüren. Doch von den nordafrikanischen Staaten, die im Planungsstadium an entscheidender Stelle in das EU-Überwachungssystem eingebunden werden sollten, fehlt die Unterstützung. Entweder sind die entsprechenden staatlichen Kontrollorgane weggebrochen, wie in Tunesien oder in Libyen, oder die Regime trauen sich angesichts der kritischen Bevölkerung nicht, der EU derartige Kompetenzen auf nordafrikanischem Boden einzuräumen.

Alle Schengenstaaten melden, dass sie inzwischen vollständig Eurosur unterstützen. Diese formelle Unterstützungsprozedur dauerte ein Jahr. Eurosur dient dem erklärten Ziel, die Bootsflüchtlinge im Mittelmeer oder bereits an den nordafrikanischen Küsten aufzuspüren. Doch von den nordafrikanischen Staaten, die im Planungsstadium an entscheidender Stelle in das EU-Überwachungssystem eingebunden werden sollten, fehlt die Unterstützung. Entweder sind die entsprechenden staatlichen Kontrollorgane weggebrochen, wie in Tunesien oder in Libyen, oder die Regime trauen sich angesichts der kritischen Bevölkerung nicht, der EU derartige Kompetenzen auf nordafrikanischem Boden einzuräumen.

EU

Eurosur extended: all participating states now connected to border surveillance system

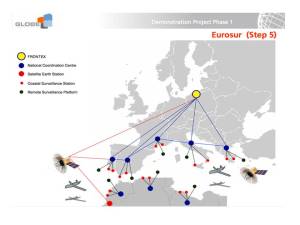

All 30 Schengen states are now connected to Eurosur, the European Border Surveillance System, which officially began operating in December 2013 with the participation of the 19 Schengen states at the EU’s southern and eastern borders.The development was noted in the European Commission’s recent report on the functioning of the Schengen area, which says: “Frontex was scheduled to connect the remaining 11 centres to the Eurosur communication network by the end of November 2014.” [1]The Commission subsequently confirmed to Statewatch that it “has received confirmation from Frontex that all the remaining Member States have been connected as scheduled.”

The new additions to the network are Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Sweden.

Eurosur is a system designed for “the surveillance of land and sea external borders” of the Schengen area to ensure:

“monitoring, detection, identification, tracking, prevention and interception of unauthorised border crossings for the purpose of detecting, preventing and combating illegal immigration and cross-border crime and contributing to ensuring the protection and saving the lives of migrants.“ [2]

Centres and pictures

According to the Commission’s Schengen report:

“During 2014, the National Coordination Centres of the remaining 11 countries have been established and all Schengen countries made progress in further developing their National Situational Pictures.”

The legislation underpinning Eurosur requires each participating state to establish:

“a national coordination centre, which shall coordinate, and exchange information among, all authorities with a responsibility for external border surveillance at national level, as well as with other national coordination centres and the Agency [Frontex].” [3]

The national coordination centre maintains the “national situational picture”, which comprises information from “the national border surveillance system”, “stationary and mobile sensors” used for external border surveillance, border patrols, and a multitude of other sources. [4]

Frontex uses the national situational pictures and other sources to establish a “European situational picture” and a “common pre-frontier intelligence picture”. The aim is to allow Schengen states and Frontex “to instantly see and assess the situation at and beyond the EU external border”. [5]

Since Eurosur’s inception, long before the adoption of the legislation that underpins the system, maintenance and development has largely been undertaken by Spanish company GMV Aerospace and Defence.

The company is the lead partner in a consortium that in December 2013 won the contract for the continued development of Eurosur, taking on the “execution, management and supervision of this 12-million-euro project over a four-year period.”

A GMV press release said “the EUROSUR project fits in perfectly with GMV’s ongoing strategy of internationalizing its defense and seurity activities and consolidates its leadership within European border surveillance activities.“ [6]

Saving lives?

Critics of Eurosur argue that the goal of saving lives is incompatible with the system’s primary purpose of border control. [7] Provisions in the legislation on the issue of saving lives were only inserted on the insistence of MEPs.

The Commission’s report on the functioning of the Schengen area notes that:

“During the reporting period, for the very first time the satellite images obtained in the framework of Eurosur cooperation enabled to save the lives of migrants. On 16-17 September, the satellite imagery obtained through Eurosur framework with the support of an FP7 project, enabled to locate the and rescue a migrant rubber boat in the Mediterranean with 38 people on board, including eight women and three children that has spent three days in an open sea and was drifting outside the area where search and rescue activity for the boat was ongoing originally.”

Whether this success will be repeated remains to be seen. A report published by Statewatch earlier this year noted: „The argument that more surveillance – in particular through drones and satellites – will improve detection of migrants’ small boats is contradicted by several studies, including one led by Frontex itself.” The article further suggested that without significant – and potentially undesirable – technological developments, “the majority of rescue operations will continue to be initiated after distress calls are made by migrants themselves.”

This may be what occurred in the case cited by the Commission – the boat in question “was drifting outside the area where search and rescue activity for the boat was ongoing originally.” Frontex deputy director Gil Aria Fernandez said in May that satellite imagery „would not be useful for preventing tragedies because the satellite images will be available hours or even days after.“ [9]

Future developments

With all states now connected to the system, the focus will be on improving its capabilities.

Next year the Commission is due to adopt a handbook, currently being prepared, that will contain “technical and operational guidelines for the implementation and management of Eurosur”. [10]

In 2014 Frontex “intensified its cooperation with the European Maritime Safety Agency and the EU Satellite Centre in providing information and services at the EU level, such as ship reporting systems and satellite imagery.”

In the coming months and years the border control agency will try to further enhance Eurosur through cooperation with a host of other organisations: Europol; the European Fisheries Control Agency; the European External Action Service; the European Asylum Support Office; the Maritime Analysis and Operations Centre – Narcotics; and the Centre de Coordination de la Lutte Anti-drogue on Méditerranée.

A draft action plan for the EU’s recently adopted Maritime Security Strategy also foresees a number of activities aimed at improving Eurosur.

The Commission will invite all participating states “to ensure that by 2015 all civilian and military relevant authorities with responsibility for maritime border surveillance share information via the EUROSUR national situational picture and cooperate via the EUROSUR national coordination centres on a regular basis.”

Participating states are invited to “second any needed Liaison Officers to the national coordination centres”; “to coordinate the patrolling activities of their national authorities responsible for maritime surveillance”; “to strengthen the cross-border cooperation”; and to promote “the best practices of interoperability between the relevant authorities in maritime security in the area of radio and other forms of communication.”

Under the heading ‚ensure adequate coordination between the various EU surveillance initiatives in the EU and the global maritime domain‘, the plan also outlines the intention to:

“Complement space-based technology with the applications of RPAS [Remotely Piloted Aerial Systems, drones] as well as ship reporting systems, in situ infrastructure (radar stations) and other surveillance tools, to ensure a global maritime awareness picture, also through the elaboration of a civil-military concept detailing specific information and operational requirements.“ [11]

Funding priorities

Funding for the development of Eurosur will be available to Member States through the Internal Security Fund: borders and visa (ISF-Borders), which was adopted earlier this year by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU, and has a €2.76 billion budget from 2014 until 2020.

According to the budget’s work programme for 2014, funding will be made available for “enhancing cooperation between Member States in the framework of EUROSUR”, which foresees activities supporting the increased gathering and exchange of information by and between Member States‘ embassies and consultates, as well as:

“Activities supporting improvement on the technical and operational capability of the Member States to detect and track small vessels with a view to preventing irregular migration and cross-border crime, as well as to reducing the loss of migrants‘ lives at the external sea borders.“ [12]

The fund will also support: “Activities aiming at supporting the information exchange and cooperation between Member States and neighbouring third countries,” which may include the development or upgrading of bodies in third countries similar to national coordination centres, as well as “joint operations, including patrolling and surveillance activities; training, studies, pilot projects.”

Further reading

- Charles Heller and Chris Jones, ‚Eurosur: saving lives or reinforcing deadly borders?‚, Statewatch Journal, vol 23 no 3/4, February 2014

- ‚Data adrift on the high seas: work continues on connecting maritime surveillance systems‚, Statewatch News Online, August 2014

- Nikolaj Nielsen, ‚EU border surveillance system not helping to save lives‘, EUobserver, 14 May 2014

Footnotes

[1] European Commission, ‚Sixth bi-annual report on the functioning of the Schengen area‚, 27 November 2014, COM(2014) 711 final

[2] Regulation (EU) No 1052/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 establishing the European Border Surveillance System (Eurosur)

[3] Article 5, Eurosur Regulation

[4] Article 9, Eurosur Regulation

[5] Frontex, ‚Eurosur‚

[6] ‚GMV wins the EUROSUR project‚, 11 March 2014; ‚Poland-Warsaw: Framework contract for maintenance and evolution of the Eurosur network‚, 18 January 2014

[7] Alois Berger, ‚Goals of Eurosur border scheme questioned‚, Deutsche Welle, 11 October 2013

[8] Charles Heller and Chris Jones, ‚Eurosur: saving lives or reinforcing deadly borders?‚, Statewatch Journal, vol 23 no 3/4, February 2014

[9] Nikolaj Nielsen, ‚EU border surveillance system not helping to save lives‘, EUobserver, 14 May 2014

[10] European Commission, ‚Sixth bi-annual report on the functioning of the Schengen area‚, 27 November 2014, COM(2014) 711 final]

[11] Friends of the Presidency Group (EUMSS), ‚European Union Maritime Security Strategy (MSS) – draft Action Plan‚, 15658/14, 24 November 2014; General Secretariat of the Council, ‚European Union Maritime Security Strategy‚, 11205/14, 24 June 2014

[12] European Commission, ‚Annex to the Commission Implementing Decision concerning the adoption of the work programme for 2014 and the financing for Union actions and emergency assistance within the framework of the Internal Security Fund – the instrument for financial support for external borders and visa‚, 8 August 2014, C(2014) 5650 final